The early chapters of Genesis and evolution

No section of Scripture has come under more sustained and vehement attack than Genesis 1–11, that part of Scripture which deals with Creation, the Fall, the Flood, and the tower of Babel. ‘Genesis’ means ‘origin’. In these chapters we have the origins of the world, of life, of mankind, of marriage, and of the entry of sin into a world that God had declared to be ‘very good’. To dismantle Genesis is to dismantle the whole Christian view of the origins.

Since Charles Darwin published his On the Origin of Species in 1859, however, public opinion has been fed, and been all too ready to believe, that the hypothesis of evolution has disproved the book of Genesis. Sir Julian Huxley has said: ‘We all accept the fact of evolution. … The evolution of life is no longer a theory. It is a fact. It is the basis of all our thinking.’1 Richard Dawkins is quite serious, and says that anyone who rejects evolution is ‘ignorant, stupid or insane (or wicked—but I’d rather not consider that)’.2 Teilhard de Chardin, a Jesuit priest and some kind of palaeontologist, has waxed eloquent: ‘Evolution is a light illuminating all facts, a curve that all lines must follow.’3 At Princeton University, Ashley Montagu has asserted: ‘The attack on evolution, the most thoroughly authenticated fact in the whole history of science, is an attack on science itself.’4 F.J.A. Hort, British New Testament Greek scholar, considered that Darwin’s book was ‘unanswerable’.5 One could multiply quotations along this line, but it is all a little strange because Darwin himself admitted in 1856 to Asa Gray ‘the many huge difficulties on this view’.6

The Church has been intimidated, and gone onto the back foot, not only about Genesis but about the whole Bible. Douglas Kelly7 has followed Henry Morris in saying that there are at least 200 quotations or allusions to Genesis in the New Testament,8 and over 100 references to Genesis 1–11 in the New Testament.9 The two Testaments fit together, and an attack on Genesis logically implies an attack on what is built on Genesis. Those who do not believe Moses and the prophets will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead (Luke 16:31). Jesus’ challenge to His opponents was: ‘If you believed Moses, you would believe Me, for he wrote about Me. But since you do not believe what he wrote, how are you going to believe what I say?’ (John 5:46–47) A rejection of the words of Moses logically leads to a rejection of Jesus who accepted the words of Moses.

The creation tells us that there is a Creator (Ps. 19:1–3; Rom. 1:20). Those who do not believe that there is one Creator of all the world need to hear that as part of hearing the Gospel (see Acts 17:24, 30–31). One who believes that we all got here by some fluke—a big bang ages ago, and hey presto, we are on the way—will not make much sense of the claims of Christ. How can one believe in the One who rose from the dead (a new creation e.g. John 20–21) unless one also believes that this One also made the world (the old creation e.g. John 1:3)? The God of the Bible is the God of nature. True science cannot contradict true theology. Sir Francis Bacon rightly spoke of God’s ‘two books’—Scripture and nature—which, coming from the same author, must be in agreement with one another.

Various Views of Creation

In the last 150 years the Church has seen a plethora of notions about the creation. The Gap Theory has been popular with some Christians, from the time of Thomas Chalmers, who died in 1847. It was popularised by the notes in the Scofield Bible, and was widely accepted in fundamentalist circles. According to the Gap Theory, Genesis 1:2 should be translated as, ‘The earth became without form and void’ i.e. there was a creation, a collapse, and then a re-creation. This leaves room for an old earth, and for a fossil record reaching back millions of years, but there is something desperate about this exegesis.

When evolution was becoming more acceptable to the general population, even conservative theologians such as B. B. Warfield and James Orr came to accept theistic evolution as compatible with biblical Christianity. In more recent times, Meredith Kline and Henri Blocher have viewed the first two chapters of Genesis as more poetry than strict science. Meanwhile, Bernard Ramm, James Montgomery Boice, and Davis Young have embraced what is called progressive creation.

The literary genre of Genesis 1–2

The Bible speaks of the four corners of the earth (Rev. 7:1) and also speaks of the sun rising and setting (Eccles. 1:5). If these descriptions are taken literally, any kind of science is set over and against the Bible. This is a warning that the Bible contains many literary genres, and is not designed to be always taken literally. For example, when Isaiah says that the mountains and the hills shall break forth into singing before you, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands (Isaiah 55:12), he is not writing a scientific treatise. The ancient Hebrews had a developed concept of poetry—and God Himself is more than willing to use poetry as a vehicle for divine truth.

This raises the issue of the literary genre of the early chapters of Genesis. Do they belong with the scientific treatises or with poetry? Sandy Grant considers that the early chapters of Genesis might best be called ‘figurative history’—‘that is, history which has artistic figurative elements which do not necessarily need to be taken literally.’10 He compares it to the parable of the tenants in Matthew 21.11 Derek Burke is another one who claims that Genesis 1 is not intended to be understood as science.12

The distinguished evangelical Old Testament scholar, Gordon Wenham, also tries to avoid a Bible-versus-science debate, and warns against those who would interpret Genesis 1-2 ‘over-literalistically’. He adds that ‘at best, all language about God is analogical.’13 Henri Blocher’s approach is somewhat similar, although, despite his detailed exegesis, it remains not altogether obvious why Adam is a literal man but the tree of life, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and the snake are not to be taken literally.14

The Six Days

There have been many attempts to explain the six days of Genesis 1. In the early Church, Origen and Augustine are often cited as two who did not believe in a literal six day creation. Origen was inclined to a much longer period, but Augustine seems to have been bewildered why God took so long. The great African father commented: ‘What kind of days these are is difficult or even impossible for us to imagine, to say nothing of describing them.’15 He thought that God probably created the world in an instant.

P.J. Wiseman tried to popularise the view that God took six days to reveal what happened at the creation. On this view, Genesis 1 is not the record of creation but the record of the revelation of creation.16 The Gap Theory tried to make room for millions of years, but it still considered that the days of Genesis 1 were literal days. The millions of years were fitted in between Genesis 1:1 and Genesis 1:2.

More popular now is the view that the days were not necessarily of 24 hours’ duration. This was accepted by evangelical stalwarts such as Hugh Miller and Charles Hodge in the 19th century, and by Edward Young and Francis Schaeffer in the 20th. John Murray thought that the days were not necessarily six successive days.

In Genesis 2:4 ‘the day’ (Hebrew ‘yom’) denotes a time period that is not 24 hours, and presumably not many believers are committed to the view that ‘the Day of Judgment’ is necessarily something of 24 hour duration. Also, the sun is only created on the fourth day in Genesis 1, so, it is sometimes said, the time frame for the first three days at least is not a day as we would measure it by the earth’s rotation relative to the sun. There are also appeals to the Psalmist’s comment that, in the common paraphrase, a thousand years are as a day in God’s sight (Psalm 90:4; 2 Peter 3:8). More recently, Hugh Ross has emerged as a more decided proponent of the view that the six days are not literal.

The most natural reading of Genesis 1, however, would seem to be that the days are literal and successive. The fourth commandment declares that we are to remember the Sabbath day, ‘for in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and hallowed it’ (Exodus 20:11). The rhythm of man’s working week is based on the creation week.

Furthermore, it is difficult to explain away the recurring expression ‘the evening and the morning’ in Genesis 1:5,8, 13, 19, 23, 31. So emphatic is this that it is hard to escape the conclusion that if God wanted us to understand the creation week as a literal week, He could hardly have made the point any clearer. It is somewhat mystifying to attach much meaning to an evening and morning of an era extending for millions of years.

The theological argument is also compelling. According to the Bible, there was no death until there was sin. The creation is cursed only after Adam sinned (cf. Genesis 3; Romans 5:12–21; 8:19–25). This implies that all the fossils of dead animals must date from after Adam’s fall. If there was blood and violence in the creation before Adam sinned, the theological structure of the biblical message would appear to suffer considerable dislocation.

This would mean that conventional dating methods have provided the wrong answers. Radiometric dating works with a number of assumptions, namely, a constant half-life, an isolated system, and known boundary conditions. There is thus an assumption of uniformitarianism (constancy of processes and rates through time). Because of the Flood, these conditions are not met, and this would play havoc with dating methods. For example, the Flood would have completely disrupted the earth’s carbon balance, which means the radiocarbon content of the atmosphere has been not in equilibrium since that time. By ignoring this effect the world would then seem to be older than it is.

It was not for nothing that the liberal scholar, Marcus Dods, stated that if the days of Genesis 1 are not literal 24-hour days, then the interpretation of the Bible is ‘hopeless’.17

‘According to its Kind’

We find this phrase in verses Genesis 11, 12, 21, 24, 25. According to the hypothesis of evolution, reproduction can lead to strange results. We started out with a single-celled creature, and millions of years later this has become a fish, then a reptile, then a bird, then a mammal, then a monkey, and finally human beings belonging to the United Nations. Genesis 1, however, implies that there is a built-in stability. For example, there will be big horses (e.g. the Clydesdale) and small horses (the Shetland pony), but horses will only beget horses.

There is an easy way to check this—look at the fossil record. If Darwinian evolution is correct, there should be transition animals everywhere as one type evolves into another. If Genesis is correct, one would expect to find no transition animals (this is not to say that Genesis’ ‘kind’ is identical to the modern term ‘species’, but that there is a locking-in mechanism). What do we find in the fossil record? Darwin himself was unable to point to any single instance of a definite graded evolutionary sequence of organisms in the paleontological record. In fact, he confessed that ‘Nature may almost be said to have guarded against the frequent discovery of her transitional or linking forms.’18 As Duane Gish has shown, the missing links between species are still missing—and missing virtually everywhere.19

Stephen Jay Gould (who was an ardent evolutionist—indeed a Marxist—and Professor of Geology at Harvard University) wrote of the fossil record and transition animals: ‘If evolution almost always occurs by rapid speciation in small, peripheral isolates—rather than by slow change in large, central populations—then what should the fossil record look like? We are not likely to detect the event of speciation itself. It happens too fast, in too small a group, isolated too far from the ancestral range.’20 Gould was passionately committed to the hypothesis of evolution, but he acknowledged that there was little evidence for slow evolutionary change: ‘The fossil record does not support it; mass extinction and abrupt origination reign.’21 Michael Denton is no creationist (as yet), but he calls evolution ‘a theory in crisis’, and writes of ‘the virtual complete absence of intermediate and ancestral forms from the fossil record’.22 In short, the fossil record supports Genesis 1, not Darwinian evolution. The missing links are missing everywhere.

Eden was a real place.

Genesis speaks of Eden as a real place, with four rivers—the Pishon, Gihon, Hiddekel (or Tigris) and the Euphrates (Gen. 2:8–14). Of the four names mentioned in Genesis 2, two are connected with rivers today—the Tigris and the Euphrates. Because of these names scholars have speculated on two main possibilities regarding the location of Eden: either where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers meet and form a delta at the head of the Persian Gulf, or where they rise in the upland plateau of what is now eastern Turkey.23 However, the Flood rearranged things quite drastically and these rivers in the Middle East are underlain by thousands of metres of Flood-deposited sediment. It’s likely the rivers were named after their pre-Flood counterparts. So, although Eden was clearly a real place within literal history, it is no longer identifiable today. But Eden was a real place and a beautiful place.

Conclusion

In the year 2000 my wife and I went into the Sydney Art Gallery to see an exhibition of the Dead Sea Scrolls. There were a multitude of advertisements for features on the creation myths of various cultures, including the aboriginal creation myths (such as the Rainbow Serpent stories) and the Genesis creation myth. The obvious problem is that Genesis 1–11 does not present itself primarily as myth or poetry. There are genealogies in chapters 5 and 10, and these are sober straightforward accounts—unlike the wild genealogical accounts to be found in Assyrian documents. Genesis is not given to us as a poetic expression of truth dressed up in allegories and symbols. There is poetry in the Bible, but this is not poetry.

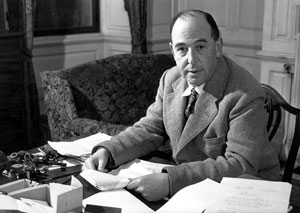

The attempt to reconcile Genesis and evolution almost invariably leads to compromise on the part of Christians. Back in 1964, the Old Testament scholar, R.L. Harris, wrote: ‘I am appalled at the freedom with which our Christian scientists are toying with the Biblical texts.’24 Interestingly enough, C.S. Lewis was one Christian who became more disenchanted with the whole hypothesis of evolution. On 9 December 1944 he wrote to his friend Captain Bernard Acworth (an ardent anti-evolutionist): ‘I can’t have made my position clear. I am not either attacking or defending Evolution. I believe that Christianity can still be believed, even if Evolution is true.’ By 1951 that tone was changing, and he wrote to the same Captain Acworth: ‘What inclines me now to think you may be right in regarding [evolution] as the central and radical lie in the whole web of falsehood that now governs our lives is not so much your arguments against it as the fanatical and twisted attitudes of its defenders.’25

The fact that God is the Creator establishes His Lordship over the world. It establishes His Lordship over you and me, and His claims on our lives. It is because He is Creator that He has the right to judge. That is why you and I are answerable to Him. He is the one to whom the Scripture testifies and to whom all creation testifies.

Acknowledgement

This article first appeared in Contending Earnestly for the Faith, Vol. 13:3, Issue 41, September 2007.

References

- New York Times, November 26, 1959. Return to Text.

- Cited in Andy McIntosh, Genesis for Today, Surrey: Day One, 1997, p.18. Return to Text.

- Cited in James Montgomery Boice, Genesis, vol.1, Michigan: Zondervan, 1982, p.48. Return to Text.

- Cited in Marvin L. Lubenow, Bones of Contention: A Creationist Assessment of the Human Fossils, Michigan: Baker, 1992, p.206. Return to Text.

- Cf. John Rendle-Short, Green Eye of the Storm, Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1998, p.124. Return to Text.

- C. Darwin, Life and Letters, edited by Sir Francis Darwin, 1898, p.437. Return to Text.

- Jordan Professor of Systematic Theology at Reformed Theology Seminary, in Charlotte, North Carolina, USA. Return to Text.

- Douglas Kelly, Creation and Change, Fearn: Mentor, 1997, p.43. Return to Text.

- Henry Morris, The Genesis Record, Welwyn: Evangelical Press, 1977, pp.21, 677–682. Return to Text.

- Sandy Grant, ‘Reading Genesis’, The Briefing, October 2006, issue 337, pp.10, 12. Return to Text.

- Sandy Grant, ‘Reading Genesis’, The Briefing, October 2006, issue 337, pp.10–11. Return to Text.

- Derek Burke (ed.), Creation and Evolution, Leicester: IVP, 1985, p.168. Return to Text.

- Gordon Wenham, Genesis 1–15, Waco: Word, 1987, pp.39–40. Return to Text.

- Henri Blocher, In the Beginning, Downer’s Grove: IVP, 1984, pp.124, 155. Return to Text.

- Augustine, City of God, XI, 6. Return to Text.

- P. J. Wiseman, Clues to Creation in Genesis, London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott, 1977. Return to Text.

- Cited in Douglas Kelly, Creation and Change, Fearn: Mentor, 1997, p.50. Return to Text.

- C. Darwin, The Origin of Species, Harmondsworth: Penguin, reprinted 1985, pp. 301–2. Return to Text.

- Cf. D. Gish, Evolution: The Fossils Say No! California: Creation-Life Publishers, 1980. Return to Text.

- S. J. Gould, Ever Since Darwin, Victoria: Penguin, 1982, pp.61–62. Return to Text.

- S. J. Gould, Ever Since Darwin, Victoria: Penguin, 1982, p.271. Return to Text.

- Cf. Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, Bethesda: Adler & Adler, 1985. Return to Text.

- Cf. E. Lucas, Can We Believe Genesis Today? Leicester: IVP, 2001, pp.130–131. Return to Text.

- Cited in Ronald F. Youngblood (ed.), The Genesis Debate, Michigan: Baker, 1990, p.79. Return to Text.

- C. S. Lewis on Creation and Evolution: The Acworth Letters, 1944–1960’, https://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/1996/PSCF3-96Ferngren.html. Return to Text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.